What is meant by ‘a proportional response’? When Israel started to pound Gaza with large bombs, TV anchors started to ask, is that a proportional response? For a long time, I kept wondering, who can answer? Who knows the mathematics to devise an equation that tells you, yes, to target one person designated as an ‘enemy’, it is ok to kill 30 additional people, but not 31. Apparently, ‘proportionality’ is important under law; you decide if an act of bombing is legal or not under international law by weighing civilian harm against military objectives, it seems. And the question still seemed to haunt, what is this dark and morbid art, this calculus of evil, whose consequences are there for all of us to behold and be bewildered by, for the horror unfolding every day does defy belief. That’s when I came across ‘The Least of All Possible Evils: Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza’ by Eyal Weizman.

Eyal Weizman is the founder and director of Forensic Architecture, which is an interdisciplinary group of architects, scientists, lawyers, journalists, who investigate corporate and state violence. As the name suggests, what they do is examine the aftermath of an act or acts of violence, by looking at ruins, maps, and other available digital and physical artifacts, and interrogate them to build a picture of what has happened. If forensic pathology tries to understand what caused someone’s death by examining their body, forensic architecture does the same by examining the material evidence of the devastation.

As Eyal Weizman and Forensic Architecture’s group is about studying and understanding violence and building a narrative around it, their work has to contend in evaluating how violence is justified; what violence is permissible. How does one decide?

Suppose you are God, and you were asked to answer the question — should there be an earthquake in Lisbon? You are a God, and you are an econonmist, and so you answer this question by solving a minimum problem in the calculus of variations, like an economist would, and choose the optimum in a combination of good and evil, and choose a course of action that is the best possible world for the future. And then issue a divine decree – let there be an earthquake.

Of course, we are not Gods. We are humans. Some form governments. Some form the bureaucracy. And we come up with different kinds of models that let us ‘calculate’ the effects of evil, of violence, in a bid to mitigate it (at least that’s the idea), and decide what is ‘The Least of All Possible Evils’. It is not a theoretical exercise, a philosophical railway engine gone awry problem that you debate. Rather, these are real people in real-life situations coming up with mathematical equations to decide what is the least of all possible evils. What Weizman iterates through the book that whatever be the rationale (one has to be pragmatic, one has to compromise, life is neither just nor fair), the least of all possible evils is still evil, something the quote by Hannah Arendt speaks of in the beginning of the second chapter. Thus, one of the central arguments Weizman makes is that ‘moderation of vilence is part of the very logic of violence’.

“If we look at the techniques of totalitarian government, it is obvious that the argument of ‘the lesser evil’ . . . is one of the mechanisms built into the machinery of terror and criminality. Acceptance of lesser evils is consciously used in conditioning the government officials as well as the population at large to the acceptance of evil as such . . . Politically, the weakness of the argument has always been that those who choose the lesser evil forget very quickly that they chose evil.1

Hannah Arendt, 1964”

In the book, Weizman charts the history of the idea of ‘lesser evil’, drawing from different domains, including theology, ethics, human rights, law, and mathematics. He starts off by talking of ‘Arendt in Ethiopia’ where he speaks of the dilemmas faced by Doctors Without Borders in providing humanitarian assistance during the Ethiopian famine of the 1980s, a crisis that involved people displaced by the famine and war, militaries and militia, the UN, aid organisations and workers. Do you provide humanitarian assistance if the promise of aid is used to lure people only to deport them? Do you withdraw aid? Or do you still provide it, for there is a famine, there are people in desperate need of aid? Do you provide aid, even though it is a strategic tool used by all sides of the conflict in different ways? Do you speak of the atrocities you witness? If you speak, you will be evicted, so what do you do? Is withdrawal a meaningful option? In discussing such thorny dimensions of providing aid, Weizman slowly unravels the complicated mess that is the question of what is deemed as the least evil option to choose, and therein lies the basis for the odd subtitle of the book, the phrase ‘humanitarian violence’.

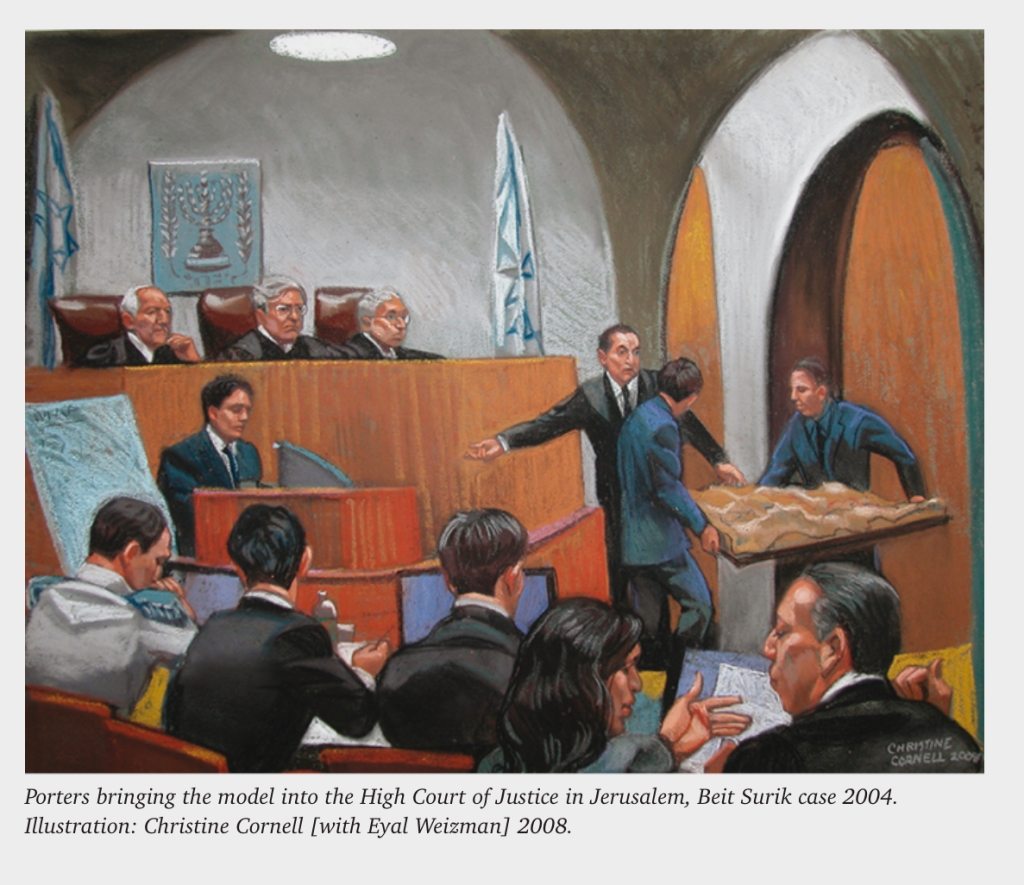

The next chapter ‘The best of all possible walls’ goes deeper into these spiky spaces, with the case of legal challenges around Israel’s separation wall. Israel wanted to build the wall for its security; the wall affected the livelihoods of Palestinians living in the West Bank, and so in order to figure out what the configuration of the wall should be, in the courts, a territorial-scale physical model of the wall was used to argue and debate. ‘Proportionality’ was used; not to decide if a wall should be built or not; but how to figure out the proportion between the security needs and the livelihood concerns. As Weizman says: “In other words, the trials were concerned with moderating the violations and violence perpetrated by the wall in the name of the principle of the ‘lesser evil’.” As someone who has worked on participatory design, this was a grotesque case to read about: The people whose lives are being violated are participating in the design of that violation. The case itself echoed the same question — by working with the Israeli legal system, you legitimise the occupation, but without working with it, you cannot mitigate the violence of the occupation.

As Weizman writes: “If the wall does ever come to designate the borders of a shrunken temporary Palestinian state, it will be the first such border to have been co-designed by humanitarian lawyers. It is in this way that the Beit Sourik trial provides a reflection on the limits of the process of ‘participatory design’ – an otherwise banal process based on pseudo-consultation within predefined limits that in this case allowed people to participate in the design of one of the instruments of their most brutal violation, repression and dispossession. And so, case by case, segment by segment, concentrating on problem-solving, moderation and consultation, a major geopolitical question was dismantled and transformed into a humanitarian issue.”

The chapter goes on to talk about ‘humanitarian minimums’ that needs to be done, how thresholds can be defined and pushed, so that it remains within the limits prescribed by humanitarian laws, so that the violence is legal and tolerated. The last chapter is about forensic architecture, where again, what is ‘acceptable civilian casualties’ and the principle of proportionality is weighed upon.

As the chapters built upon each other, the enmeshed nature of military, humanitarian efforts, human rights laws, mathematical models, and architecture when it comes to violence became more clearer, and more complicated. There continue to be people who step into this web, get tangled, and yet, try to figure ways to snip at it and move. Yes, there is movement — how far and how much is the nature of the struggle.